Printing results had long been on the wish list of manufacturers of four-function calculators. While it is easy to provide a printing mechanism for machines that simply add and subtract, it is a different story when a moving carriage appears. Most technologies that combined these proved to be a commercial fiasco. However, this did not stop some manufacturers from trying.

It was only much later, in the 1950s and 1960s, that much further automation of adding machine technology brought multiplication and division within reach of what were essentially still printing adding machines (see, for example, the Olivetti Divisumma 24 and the Lagomarsino Totalia 8381).

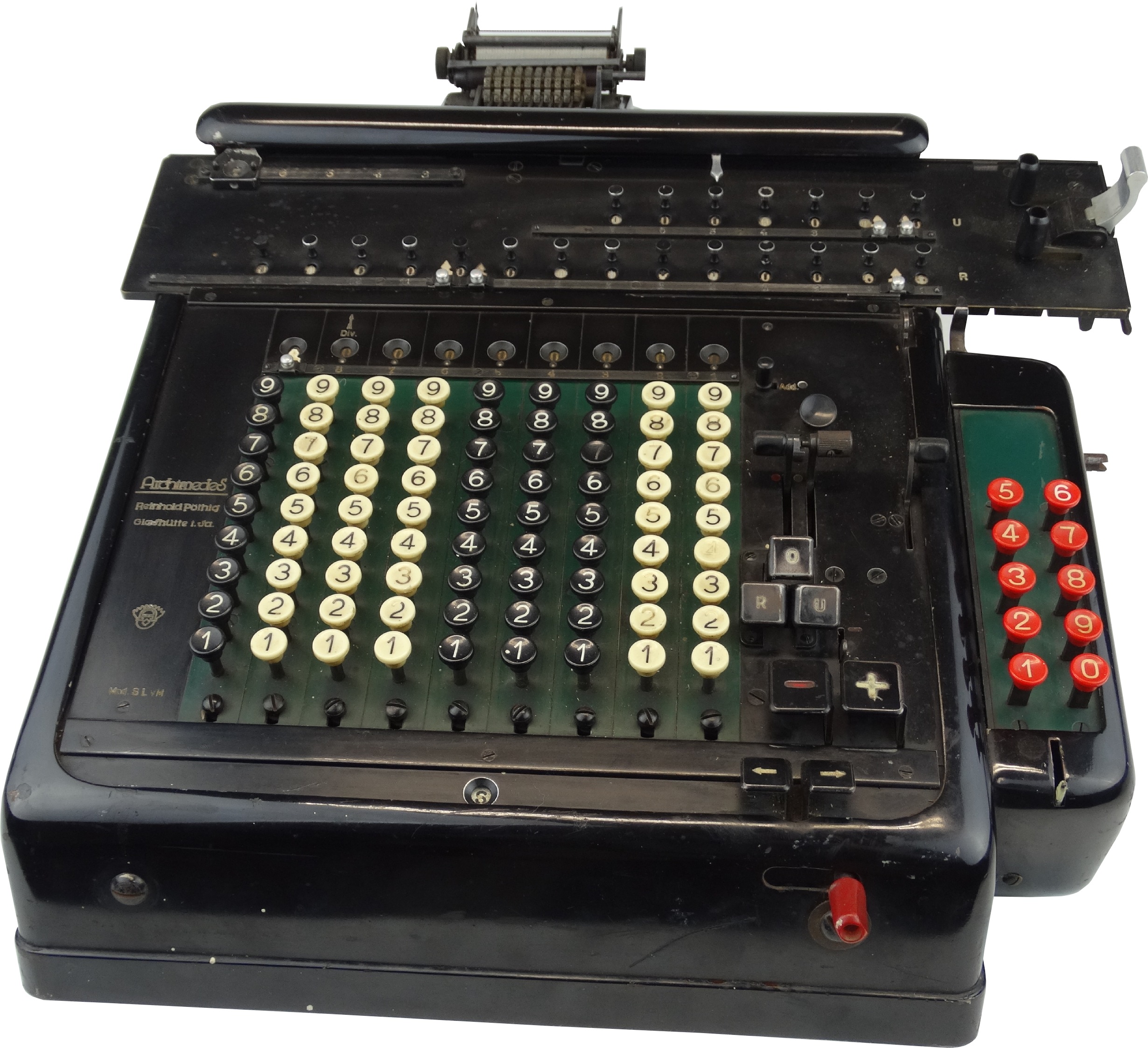

s/n ?, Glashütte, Germany, ca. 1938

This machine by Archimedes has been fitted with a printer. While adding machines can easily have a printer as their (only) output, in a four-function machine, this is far from obvious. This electric Archimedes with a number of automatic functions has a special delay mechanism built in, operated by the red sliding lever at the front, which slows down the machine by a factor of 4 when a printout is required, in order to keep the printout legible and the mechanics of the printer intact and undamaged. However, to print the result of a calculation, it had to be re-entered manually on the keyboard. This can be described as cumbersome at the very least...

Collection: C. Vande Velde

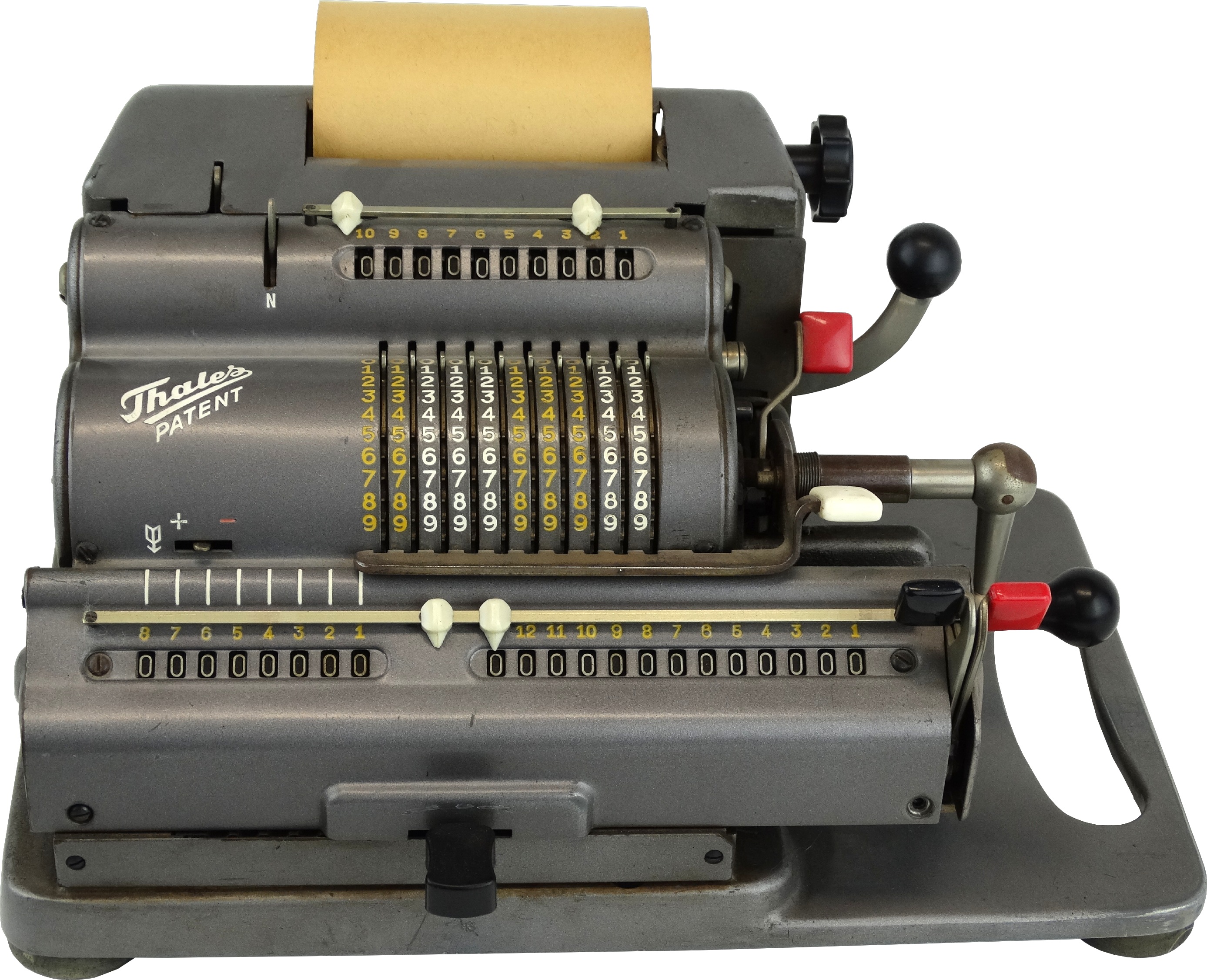

s/n 155115, Rastatt, Germany, ca. 1951

From time to time, even on pinwheel machines, attempts were made to add a printing mechanism, the first being Brunsviga's "Arithmotyp" in 1908. As with the Leibniz cylinder machines, it was only possible to print from the setting register, and thus the results of the calculations had to be transferred back to the setting register. Mechanical solutions were found for this as development progressed, so that this transfer was no longer entirely manual. This Thales machine was sold as a kind of pseudo cash register to a small grocery store in Germany. Judging by the wear and tear, it was never used very often or for very long, because, of course, it was not very practical.

Collection: C. Vande Velde

Ivrea, Italy, ca. 1968

A much better approach to printing the results of calculations was to thoroughly automate more functions and provide algorithms for multiplication and division in adding machines. This Olivetti Divisumma 24 is not only a style icon designed by the artist Marcello Nizzoli, but also offers multiplication and division functionality. This increased the complexity of the machines exponentially. This example is unsold "new old stock" and came in the original unopened wooden box found in a storage container in the Netherlands.

Collection: C. Vande Velde

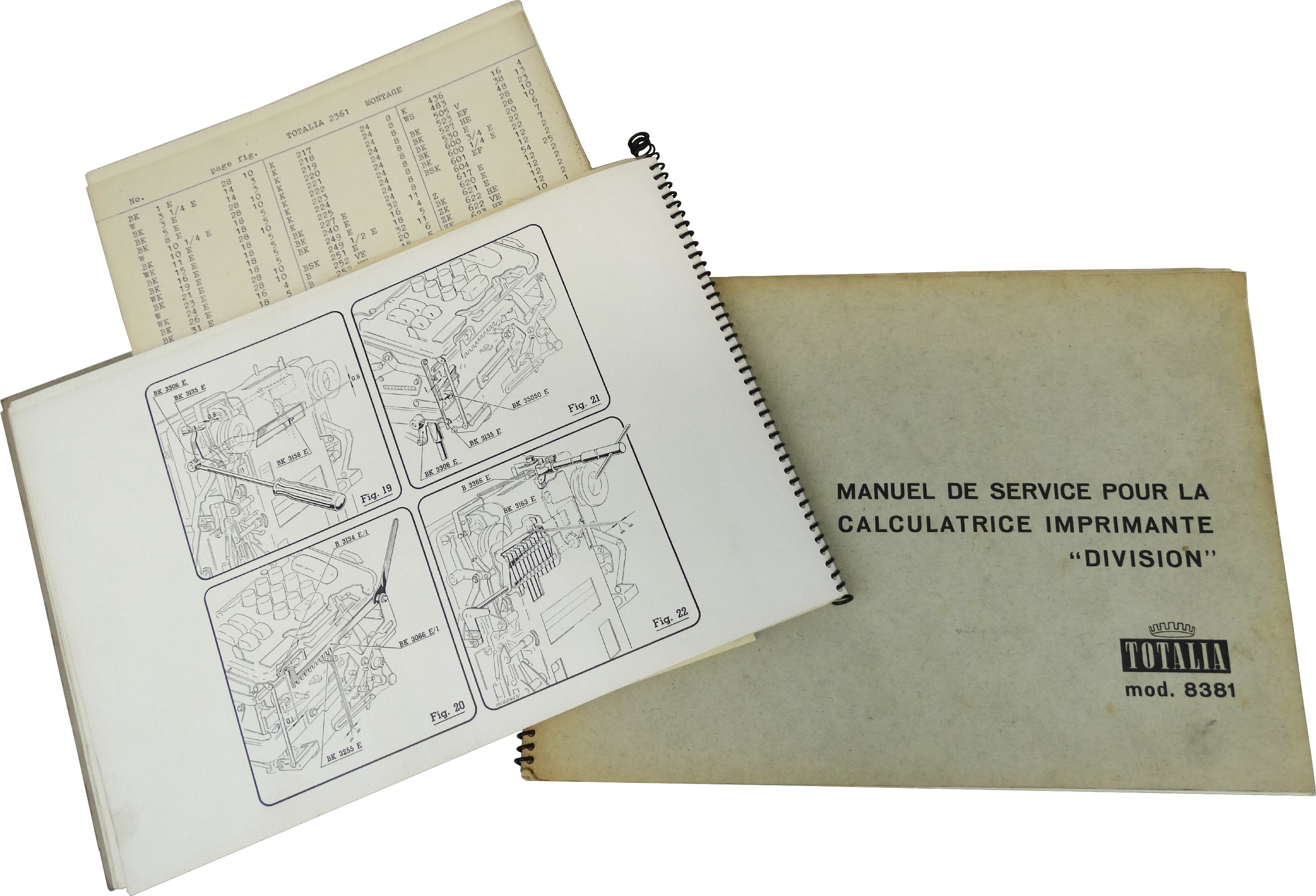

Lagomarsino, Milan, Italy, ca. 1961

This "undressed" machine shows how complicated the last generation of mechanical calculating machines had become. Pierre Vlerick, an office machine mechanic at Modern Office in Ghent, who owned this demonstration machine, explained that from an empty base plate to a fully assembled machine, 17 critical adjustments (timing angles and spring tensions) had to be made in succession - if any one of them was off by more than a few per cent, the machine would never calculate correctly. Dismantling and reassembling such a machine without the workshop and adjustment manuals and the appropriate specialist tools and equipment is no longer a job for the informed layperson.

Collection: P. Vlerick

for the Totalia 8381.

Collection: P. Vlerick