Around 1850, Thomas de Colmar (that is his surname by the way, his first names are Charles Xavier) began, more or less in earnest, the serial production of calculating machines, in his workshop in Paris.

He took it rather badly that his machines were ranked only second on the National Exhibition in 1849 as well as on the Great Exhibition in the Crystal Palace in London in 1851, while the machines of Maurel & Jayet and Staffel respectively were ranked ahead of him. He probably believed that his 1820 patent made him the first and only "father of the calculating machine". As a director of an insurance company, and therefore with a very good idea of how calculating machines could help in that business, he started a very intensive promotional campaign, gifting many machines to heads of state and other dignitaries, in order to be recognized in this way. In return, he received a large number of titles, honors and medals.

For the 1855 World Exhibition, a giant calculator the size of a buffet piano was built, so that the gold medal would certainly not elude him anymore ... unfortunately, the medal went to Scheutz's difference engine. (see 17th-19th century).

Thomas de Colmar's workshop was the only manufacturer to produce around 800 arithmometers by the time of his death in 1870. It turned out, however, that while the Staffel and Maurel & Jayet machines died a quiet death, the Thomas arithmometer had a great future ahead of it - until 1878, the Thomas de Colmar company had a virtual monopoly on the manufacture of calculating machines, until Arthur Burkhardt in the Black Forest started making copies and improving on the machines. And imitation is of course the highest form of flattery...

For a period of about 40 years, the Leibniz cylinder reigned supreme as far as calculating machines were concerned, just at the time when more and more institutes and companies became convinced of the usefulness of a calculating machine. After the advent of the pinwheel machine, the main concern was to improve the capacity of the Leibniz stepped cylinder machines to do things that were impossible with a pinwheel machine.

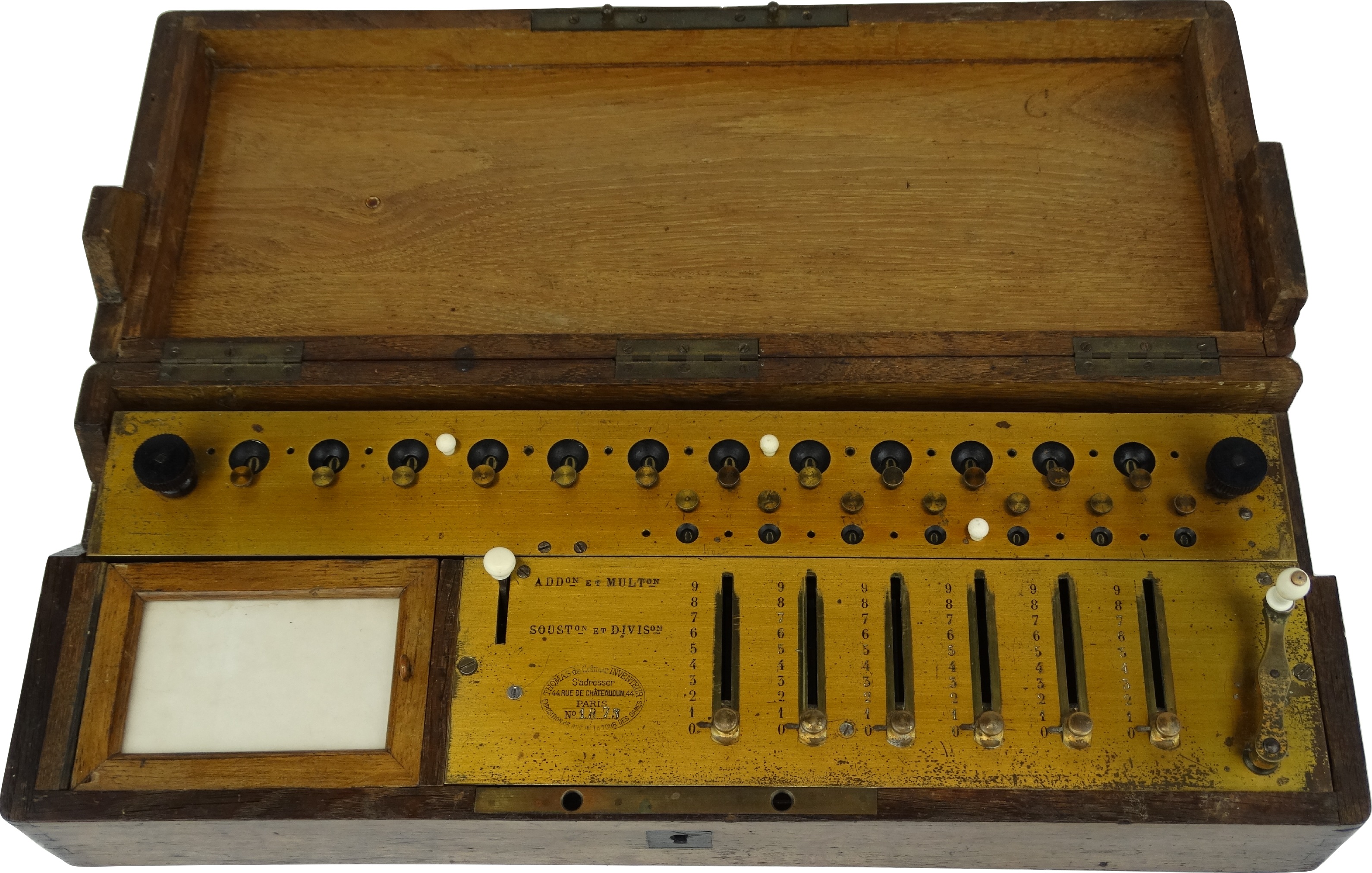

s/n 1873 (ca. 1881).

This is an example of the 1865 perfected model of the Leibniz cylinder calculator, that was developed from 1820 on by Charles X. Thomas de Colmar, which became the world's first commercially successful calculating machine, and was widely copied in later years.

Collection: C. Vande Velde

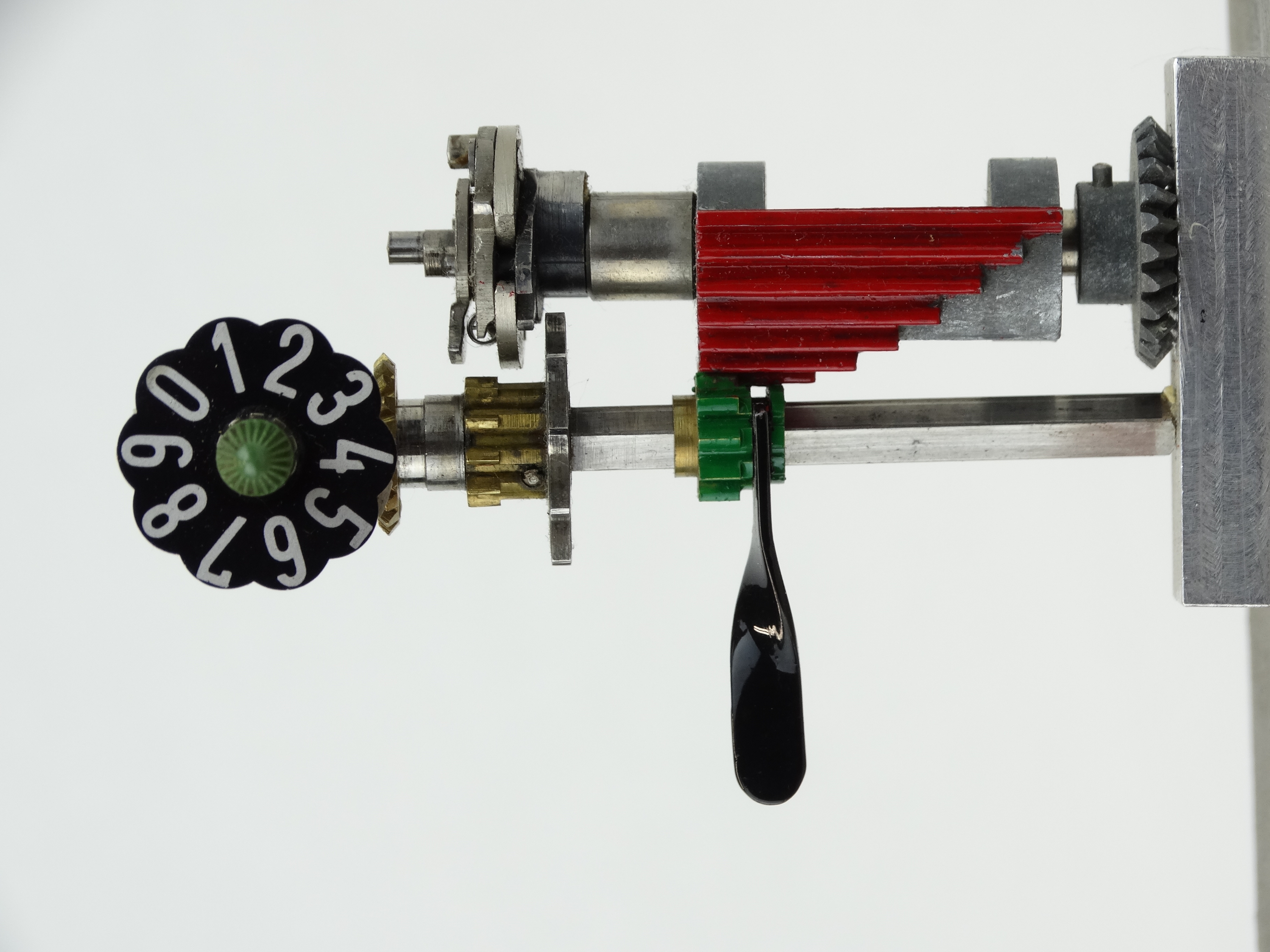

Shifting (and thus setting) the small green gear along the cylinder will result in 0 to 9 teeth on the cylinder engaging the gear on a full rotation of the cylinder.

Collection: C. Vande Velde

Leibniz spent 40 years developing his more sophisticated calculator (1694) for the four main operations. The machine never became commercially viable, but the 1694 machine has been preserved and is housed in the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Library in Hanover. It was recovered from an attic in the late 19th century and restored by Arthur Burkhardt, an early German calculating machine pioneer.

In the exhibition a non-functioning replica (built by Robert Guatelli) from the collection of the Arithmeum in Bonn is on display .

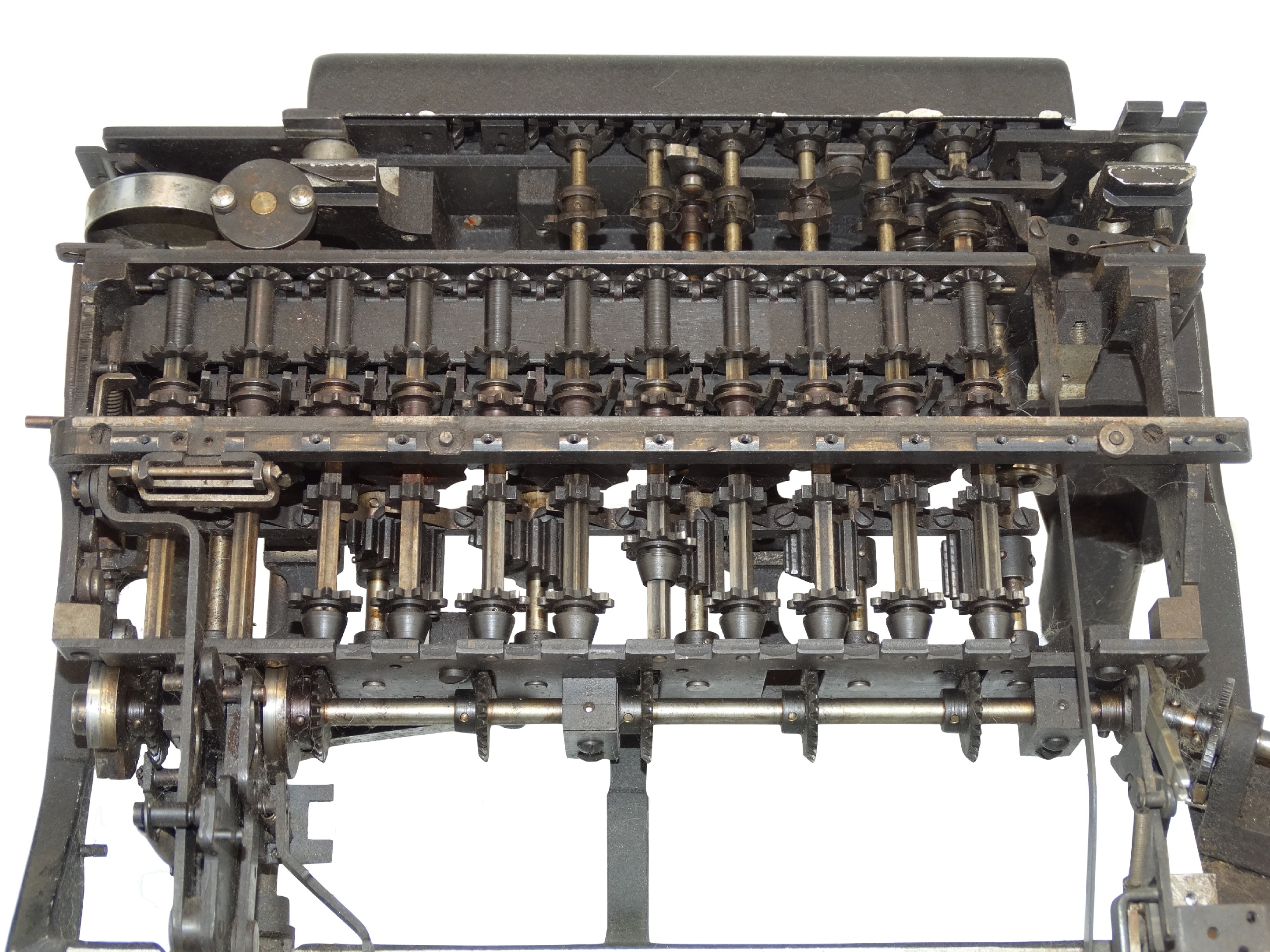

The machine does not function entirely intuitively (all tens’ carries happen at exactly the same time, so if several carries take place in successive decades, several cycles of the machine are needed to make them all happen. Fortunately, the machine gives an indication when this is the case). In principle, however, it worked, and it was possible to perform all four main operations fully mechanically, correctly and without error.

Collection: Arithmeum

(ca. 1909)

Improved Leibniz cylinder machine with setting register control and a double set of independently moving carriages that can be used as an additional memory or totaliser. There is also a simplified reset function using pull levers instead of knobs to be turned.

Collection: C. Vande Velde

(ca. 1935) The Leibniz cylinders are clearly visible. In this machine, each Leibniz cylinder operates two columns of numbers, a remarkable simplification that made production cheaper (and was obviously patented).

Collection: C. Vande Velde

French export of the brand Rheinmetall. (ca. 1935).

The machine is the result of “creativity” in a French coal mine. The large carriage with extra memory and item counter was normally only supplied on the electric machines. However, it was fitted to a manual Rheinmetall by a local engineer when the electric motor broke down. Compare with the bare chassis. The machine has a keyboard with automatic reset instead of the cumbersome slider setting, which made also summation practical with this machine.

Collection: C. Vande Velde

Developed by the Austrian calculator manufacturer Curt Herzstark, during his detention in the concentration camp Buchenwald. He was allowed to draw the machine in the camp in order to “present it to the Führer after the final victory”. The machine was built between 1949 and 1970 in Liechtenstein, by the Contina company. This machine has only one central Leibniz cylinder for all columns, but that is at the expense of legibility of the results. It was the first “pocket calculator”.

Collection: C. Vande Velde

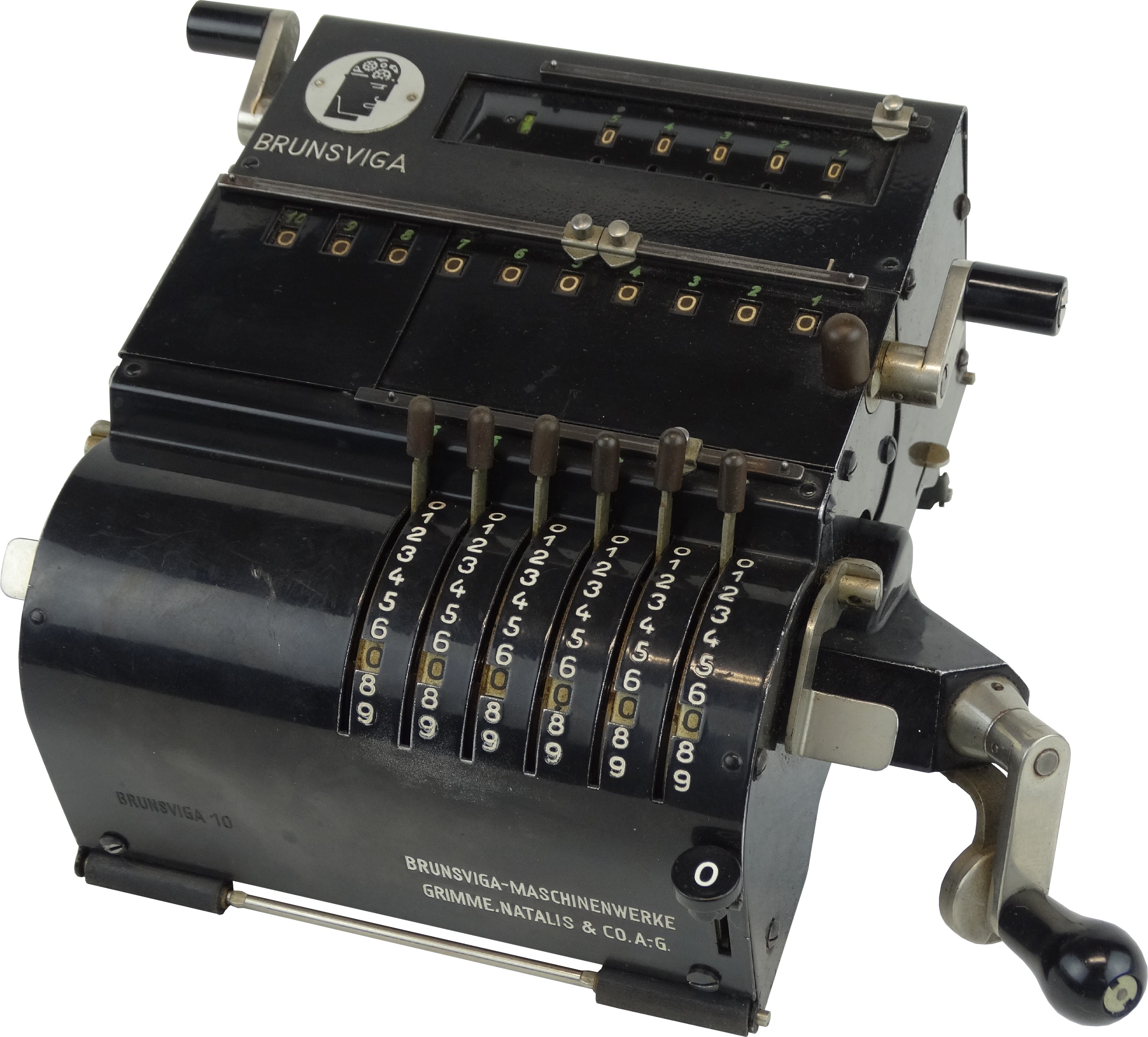

s/n 170403 (1937)

Although the firm Grimme, Natalis & Co. was the pioneer of the pinwheel machine in Western Europe, in 1932 they decided to develop a miniature machine based on a (special form) of the Leibniz cylinder. The machine is much lighter than anything else in the Brunsviga range, has non-moving setting levers and resetting of the input at the touch of a button. It runs very lightly, but has a lower capacity than the Brunsviga pinwheel machines.

Collection: C. Vande Velde