INSIGHT aims to use recent advances in Artificial Intelligence (language technology and computer vision) to support the enrichment of art collections with descriptive metadata. Multilingualism is a crucial research aspect in this respect. For the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium it is very important to be able to offer the entirely bilingual collection database (DU – FR) in a trilingual way (DU – FR – EN). The INSIGHT project responds to this by focusing on automatic title translation of works of art.

It is not easy to tackle title translation within the art sector, even for experienced translators. Deploying machine translation for this purpose is effectively a major challenge. In some cases, visual data can help (via multimodal learning, combining computer vision and natural language processing). In this respect, we mainly think of old masterpieces with descriptive titles for more realistic scene depiction. For modern and contemporary art, the use of visual context becomes more difficult, as the link between title and work of art is often less obvious.

Methodology

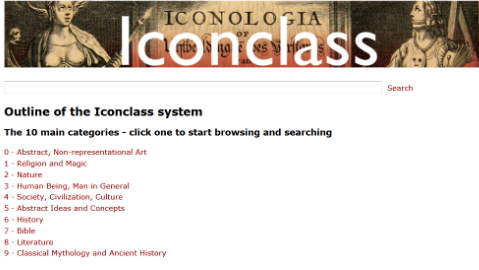

The Departments of Linguistics and Literature at the University of Antwerp, which deals with these issues in the project, obviously does not aim to compete with commercial translation masters who have unlimited computer power. The team wants to tackle smaller, domain-specific datasets and experiment with other translation techniques such as ‘character level translation’ and ‘multimodal learning’. A number of papers were recently published in this area, setting the stage for the application of these methods “in the wild”, i.e. for actual digital collections in the GLAM sector. Character-level machine translation seems very promising in this respect, although this is computationally challenging. Interestingly, we can directly inject domain-specific knowledge that is available about artworks, such as IconClass-codes, to improve the results .

Within our specific subproject, Dutch titles form the basis for the English automated translations. The algorithms need to be trained with sufficient data for this purpose. They were pre-trained on the large EuroParl corpus and then trained with RKD datasets and some 1000 titles from the RMFAB collections which are already have available in English. Initial tests show that, as was to be expected, a much as possible sector-specific training data is needed to achieve an optimal result.

Challenge in Consistency

In order to be able to provide additional material to help raise the learning curves of the algorithms, the Museum needs to review its internal linguistic conventions (e.g. to use gender neutral terms: De Baadsters -> Bathers; to avoid initial articles, unless it is commonly used and confusion could result if it were omitted: e.g. Het meisje -> Girl; to use Self-Portrait instead of Autoportrait…) and to apply those to the existing datasets and new data input to deliver. One cannot expect the algorithms to deliver good quality if the training data shows inconsistencies. The consistent application of internal conventions is moreover important both in the initial allocation of titles (in DU and FR) and in the translation of titles.

In addition to cleaning up the existing datasets, the regulatory framework will form the basis for the volunteers who are willing to translate large quantities of titles into English in order to provide the algorithms with new training material. It is, of course, essential and inevitable that future automated title suggestions will have to pass the all-seeing eye of the curators. They will make the final adjustments to arrive at official titles validated by the Institution. Through INSIGHT we hope to, at least, facilitate the translation process by offering a first basic translation.

By: Lies Van de Cappelle (Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels)