The system that gave the mechanical calculator its real breakthrough was the pinwheel. Like many good ideas, it appeared in several places at once. By making mechanical calculators much lighter and more compact, the invention of the pinwheel was the first step towards making the calculator a mass product.

The first pinwheel, or wheel with an adjustable number of teeth, was sketched as a concept by Leibniz, but without the much-needed detail of how exactly to make these "moving teeth" move.

In the 19th century, two separate inventors came up with the pinwheel and patented it in the USA - Frank S. Baldwin in 1875 and Willgodt T. Odhner from Russia in 1878. Baldwin was convinced for the rest of his life that Odhner had stolen his invention, although there is no evidence that Odhner knew of Baldwin's discovery before filing his own patent. The Englishman David Isaac Wertheimber, long before either Odhner or Baldwin (in 1843), patented a pinwheel which is surprisingly similar to Odhner's example. This machine was probably not realised - at the Great Exhibition of 1851, Wertheimer presented some simple disc adders, but nothing that worked with a pinwheel.

From 1892, after the purchase of the Odhner patent by Grimme, Natalis & Co (Brunsviga), the pinwheel machine took off. It was only when electrification and automation, and in particular the introduction of the keyboard, made calculating machines more complicated that other systems regained the upper hand. The hand-operated pinwheel remained popular until the end of mechanical calculating.

In addition to the stepped drum or Leibniz cylinder, Leibniz also invented the principle of a gear with extendable teeth, the so-called pinwheel. This sketch by Leibniz (before 1676) shows this principle ("Six Roües de Multiplication avec des dens mobiles, chacune à neuf dens").The machine was never built, and the sketch does not show how Leibniz would have made the teeth "mobile".

Photo: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Library, LH XLII, 5, Bl 29r.

Patent drawing of Swiss patent 4578 "Verbesserte Rechenmaschine" by Willgodt T. Odhner (filed 21 November 1891) showing the final production version of his pinwheel machine (left) and Frank S. Baldwin's 1875 patent US159244 (right).

The latter also patented a calculator with adjustable teeth, in his case, however, the teeth are sprung. The machine never became a commercial success, but a prototype is preserved in the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC.

This example is from a Postalia franking machine for letters. The figure on the left clearly shows how, in the upper half of the pinwheel, a rotating cam wheel pushes out four of the nine cams (teeth). The figure on the right shows the back of this wheel with the four teeth at the top.

Collectie: C. Vande Velde

Apart from the prototype of 1874 and the pre-series of 20 machines of 1877, which differed in construction, this is the first commercial form of the Willgodt Odhner machine of 1889. It was made in St Petersburg and sold in Russia and Sweden. The serial number of this machine is 318.

Collection: C. Vande Velde

Odhner's patent was sold to the sewing machine manufacturer Grimme, Natalis & Co in Braunschweig, Germany, who thought that manufacturing a calculating machine could be quite lucrative and thus began production in 1892. Franz Trinks was the driving force behind the project and helped the company grow into one of the largest calculator manufacturers in Europe (and the world). While Odhner's machines stayed true to the original design for a very long time, Franz Trinks continued to invent, design and implement innovation after innovation.

Collection: C. Vande Velde

This is the flagship model Brunsviga from 1908, only 16 years after the first model in the Odhner patent. The machine has non-rotating setting levers, two result registers (one of which can be switched to complements), a rotation counter with tens' carry, and another one without. All of this for the price of 1250M, or the equivalent in 2022 of about 8400€. The machine weighs 37kg.

Collection: C. Vande Velde

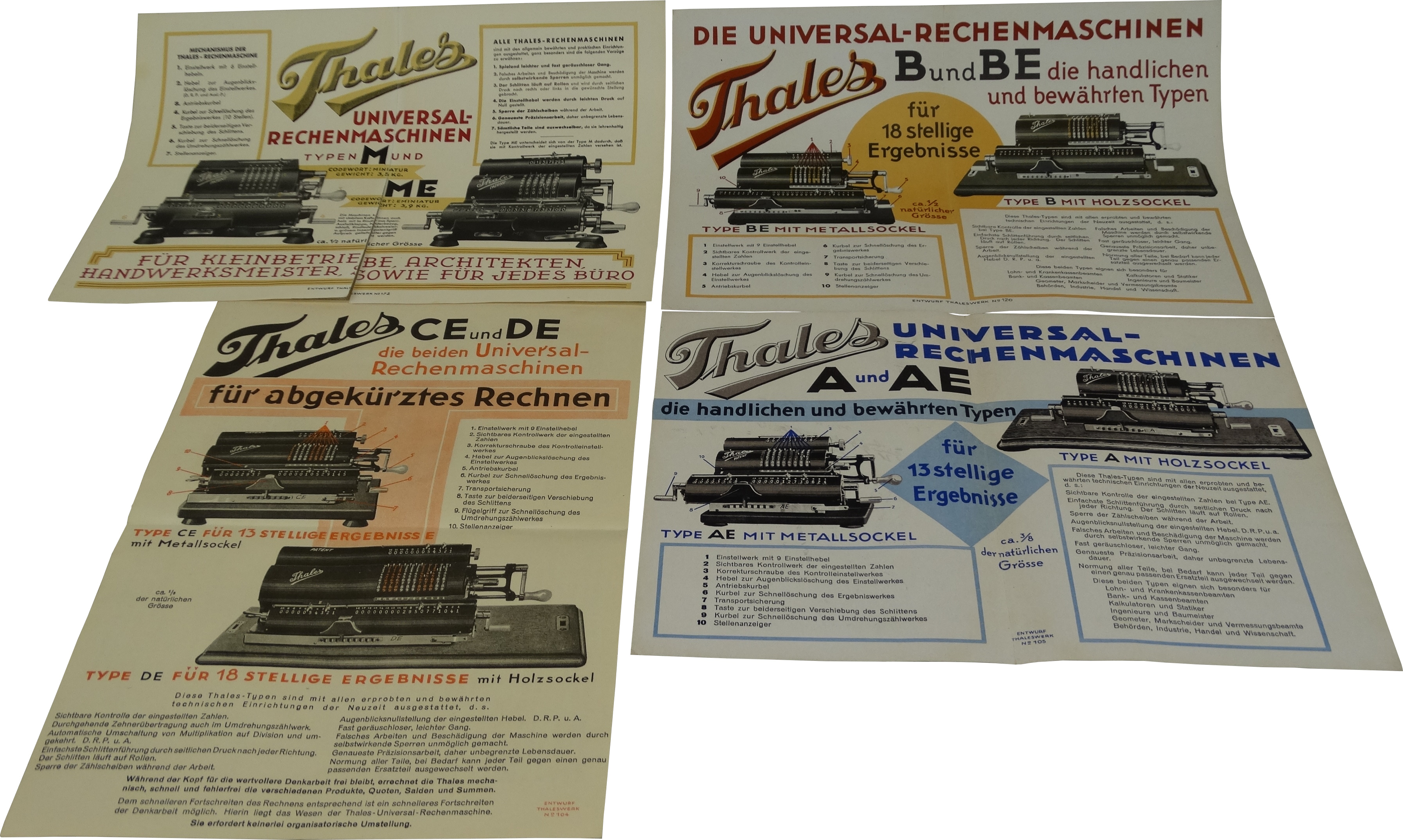

A large number of other manufacturers/brands marketed these pinwheel machines. Thales was a manufacturer from Rastatt. After the Great War, feelings towards Germany had not settled down quickly everywhere. Certainly in the UK the sale of German machines was perceived as problematic and a distributor was sought to sell the machines under their own label (Muldivo). Note the tiny engraving below the serial number on the front right of the machine: "foreign".

Collection: C. Vande Velde

Many calculator manufacturers produced colourful brochures or other promotional items or gadgets to place their machines in the frame of famous mathematicians (Thales, Euklid, Archimedes, ... or "masters of calculation") or to make it clear that they could play the role of "calculator", e.g. the "steel brain" with gears by Brunsviga, the funny "Facit-man" who also often appears in the manuals of the machines. There are perpetual calendars for Brunsviga, a tape dispenser and a calendar in the shape of an Addo X machine, stamps by Seidel & Naumann, matches with the Walther poodle and a pencil sharpener that looks suspiciously like a Walther machine.

Collection: C. Vande Velde